Written by Dave Scott

As featured on page 45 in the December 2011 issue.

INTRODUCTION: When most people learn to drive a car, they work hard at keeping the car going straight. This is mostly because of holding in the steering wheel corrections too long and trying to “steer” the car straight.

After a while, we’re able to keep the car straight with little effort because we start appreciating that most deviations can be corrected with a simple little nudge upon the wheel, and we’re confident that if one nudge doesn’t do the job, we can always apply another. Thus, applying small nudges to the steering wheel produces straighter lines and reduces the number of corrections we have to make.

Small, brief (not held in) bumps of aileron or rudder have precisely the same effect, helping us fly straighter lines, as well as making small course changes without overcontrolling.

Bump Applications: Proficient pilots use small bumps of aileron to keep the wings level to maintain straight lines. Bumps are also used to bank the wings slightly and cause an airplane to drift to the left or to the right (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: Straight lines are maintained using small (brief) aileron bumps to keep the wings level. Small course changes are made using a small bump of aileron (in and out) to bank the wings slightly. As long as the bumps are not too large or held in, the airplane won’t lose altitude after a bump, so there is no need for elevator when making small course changes. (Note: If the airplane features a symmetrical airfoil wing, the course change after an aileron bump will tend to be more gradual. To affect a more deliberate course change with a symmetrical wing airplane, the pilot must also pull a little up-elevator, and perform a mini procedure turn [Figure 2].)

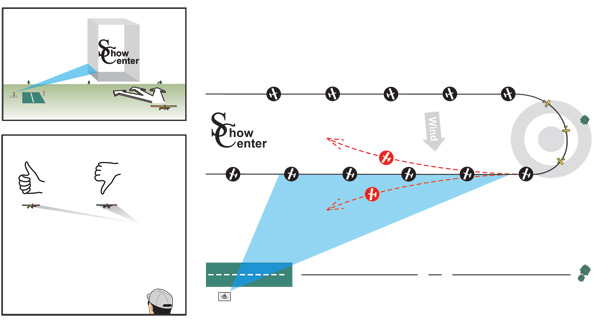

FIGURE 2: Small course changes with symmetrical wing airplanes entail briefly bumping the aileron (in and out) to bank the wings slightly, then holding in a small amount of up-elevator to effect a gentle turn. Because the bump is small, it must be applied and returned to neutral smoothly to give the airplane time to respond. Quickly jabbing the aileron will likely produce little or no response. Keep in mind that the slight wing bank and gradual course change after a smooth, small bump may not be immediately obvious. You must pause for a few moments after each bump to be certain whether another bump is needed. Often, a single bump is enough. Remember, overcontrolling is usually not caused by aggressive inputs at first, but is the result of holding an input in too long, and occurs most often when pilots hold in their inputs waiting to see an obvious reaction of the airplane. As a rule, it’s better to make two separate bumps, rather than holding in the aileron. Bumping the rudder on airplanes without ailerons works as well; however, rudder bumps must be applied smoothly to have the desired effect. The bump technique works great for gradual course changes up to 20° to 30°. A larger course change requires a deliberate turn involving aileron and elevator. As pilots (like drivers) become more relaxed, they start noticing deviations from the intended path the moment they occur, and the corresponding bumps become so small that anyone watching won’t be able to tell that corrections are being made. That’s one of the main reasons why good pilots make flying look so easy. Flying Better Straight Lines and a Parallel Foundation: If you have ever watched proficient pilots fly (you can tell by their ability to perform one maneuver after another), you may have noticed the absence of visible corrections between their maneuvers—often referred to as “being smooth.” The primary reason for their smooth flying is that they possess a solid foundation of flying consistent lines parallel with the runway. Establishing a parallel foundation starts with picturing where you want the airplane to be when it passes in front of you, otherwise known as “Show Center.” Then, project that distance out to your left and right parallel with the runway and pick some ground reference targets on the horizon to use as parallel turnaround points (Figure 3). Guiding your airplane toward these points will improve your consistency in the air.

FIGURE 3: To improve your consistency and ease of flying, picture where you want the airplane to be when it passes in front of you, then project that distance to your left and right parallel with the runway and pick some ground references to use as parallel turnaround points. Crosswind Positioning Basics and Objects as a Whole: As a rule, an airplane will fly in a straight line whenever the wings are level. When a crosswind exists, the airplane will crab (point) into the wind a bit, but as long as the wings remain level it will continue to track straight. From the ground, the position of the wings can be difficult to judge. Rather than relying on the positions of the wing or fuselage, proficient pilots concentrate on where the airplane is traveling (Figure 4a and 4b).

FIGURE 4A

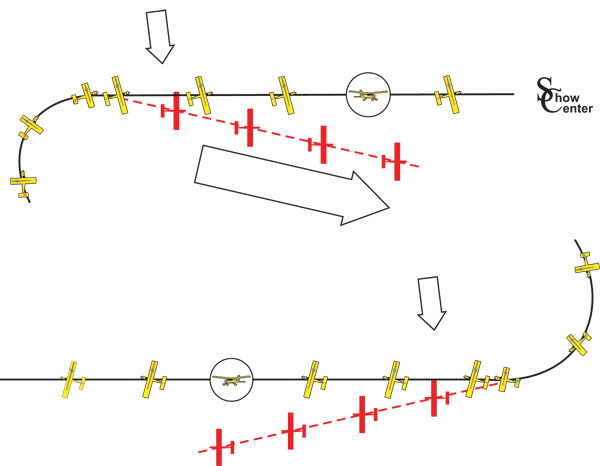

FIGURE 4B: An airplane will fly in a straight line when the wings are level. Flying in a crosswind causes the fuselage to crab into the wind, yet as long as the wings remain level, the airplane as a whole will continue to fly in a straight line. Pilots need to pay attention to where the airplane is traveling as a whole, not where it is pointing. It is easy to see deviations when guiding the airplane as a whole toward a distinct target on the horizon. It’s trickier on the return path to Show Center. Early detection of deviations from parallel, after turning around, is accomplished with an eye on where the airplane is traveling relative to you. Ask yourself, “Is it drifting away from me?” (Bump it in.) “Is it drifting toward me?” (Bump it out.) When neither a deviation in or away from you is detected, the airplane will be tracking parallel with the runway (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5: When the airplane is neither veering in nor away from you approaching show center, it will be flying mostly parallel with the runway. While wind is often blamed for deviations, it mainly exaggerates deviations and mistakes that pilots can otherwise get away with in calmer conditions. For example, when a crosswind exists, amateur pilots often make the mistake of completing their turns when the airplane points where he or she wants it to go, then inputting a crab into the wind after detecting wind drift. The correct method is to finish turns a bit early or late so that the required crab angle into the wind is already in place. That way, the airplane never gets blown in the first place (Figure 6). How early or late this happens depends on the strength of the crosswind.

FIGURE 6: When turning into a crosswind, exit the turn a bit early to establish the necessary crab angle and prevent getting blown, or overshoot the turn slightly when turning with the wind. A note to beginners regarding left/right confusion when the airplane is approaching show center: Consider the fact that a person driving a car doesn’t have to think about whether to apply a left or right input. Because the driver is facing in the direction that the car is traveling, all he or she has to do is move the steering wheel in the direction he or she wants the car to go. Rotating your body to face in the general direction the airplane is traveling, and thinking in terms of bumping the control stick in the direction that you want the airplane to go, helps reduce left/right confusion when learning to fly (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7: To reduce left/right confusion, face in the general direction that the airplane is traveling so your left and right match that of the airplane. Note that body rotation will naturally start disappearing within a few days as you shift from thinking about your own orientation to thinking about guiding the airplane as if you were in it. Conclusion: Most RC pilots continue to fly using the techniques they learned early on, including the habit of making constant corrections. Most pilots make three to four times more control inputs than what’s necessary when the airplane is flown correctly, but they are simply too busy making corrections to realize it. Not only does learning to bump one at a time improve consistency and reduce overcontrolling, it significantly improves landing because of the importance of making small inputs when low to the ground. Happy landings!

Comments

very good artical. love dave

very good artical. love dave scott's work. looking to get reprints for my grandson's

Nice Job

Dave - appreciate your excellent article on flight basics. We all share the need to sharpen our flying skills

David Scott

I took David Scott's Solo course back in 1993 and it was the best investment I ever made in my RC flying career. Not only is Dave professional in his approach to teaching one to fly RC planes but he takes the time necessary for one to fully understand the whole concept of RC flying from the basics of flight to the time one solos. I highly recommend his courses.

Mastering Straight lines & Course Adjustments

I'd like to Take this Moment in Time to show my appreciation for all the hard work the person has put in to these pages and program to teach people like myself . This program is so easy to understand & thank you for taking my training to the next level.

Excelent Training Aid

Found this to be a very interesting training aid to practice out on the air field.

Crosswind Flying

Thans for the great article David. I look forward to reading everything you write. As a flyer who took 20 years off and am now getting back into the sport, you experience and knowledge are greatly appreciated!

Add new comment