These forerunners of modern RPVs helped train WW II gunnery crews to shoot down enemy aircraft

By Hugh Maxwell

As seen in the July 1992 Model Aviation.

The Army called them OQs. The Navy called them TDDs (Target Drone, Denny). By either name they proved to be highly effective training tools.

The World War II antiaircraft gunnery crews loved them. Until then, the men had pretty much been limited to towed target sleeves for practicing their aim. These sleeves had several drawbacks. They flew only in a straight line. They didn’t look like airplanes. And you couldn’t be sure you’d hit one until someone reported the color of the paint around the bullet holes in the sleeve.

With the advent of radio-controlled miniaturized target planes, the gunnery crews had a chance to practice on something that looked, sounded, and acted like full-scale airplanes. At about one-third the size and one-third the speed of a full-scale plane, a drone at 200 yards’ distance approximated a full-size pursuit plane at 500 yards and could simulate all maneuvers and attack conditions of its larger counterpart.

The RP-4 on an early twin-rail launcher (1939). The USAF bought 53 of these target drones, designated OQ-1. Do any still exist?

The forerunners of modern RPVs, these scaled-down RC target planes offered some of the excitement of combat with no one of the obvious drawbacks. The gunnery crews could hardly wait to get at them. Watching a drone’s 100-octane gas tank explode was very satisfying, and shooting off a wing and then watching the drone spin in made the day worthwhile. Even better was a hit that set the target plane on fire and simultaneously opened the parachute so that the burning hulk floated gently down to the water.

The pioneering genius behind the remote-control aircraft industry in America was a multitalented aviation enthusiast named Reginald Denny. Though better known as a Hollywood movie start, Denny, born in England in 1891, was also a sportsman pilot, an aerial gunner in the Royal Flying Corps in World War I, and an RC model enthusiast who owned a Hollywood model airplane shop. In addition to performing for the silver screen, Denny sang baritone in a traveling opera troupe.

The first target drones produced by Reginald Denny’s Radioplane Corporation. Unlike the catapult-launched Navy versions, called TDDs, the Army OQ-2 version, shown at the left, was equipped with landing gear. At right, the Army’s OQ-3 came off production lines in early 1944.

Denny demonstrated the first RC target drone, RP-1, for the U.S. Army at Fort McArthur, California, in 1935. A nine-foot, high-wing balsa-and-plywood design, it was fitted with a 2-1/2-hp engine spinning a single, two-bladed propeller. Control was marginal, and the model crashed during the demonstration.

Reginald Denny, pioneering genius behind the WW II target drones, with the RP-1. The granddaddy of them all, this model crashed while being demonstrated to the Army in 1935.

This was followed in 1938 by the RP-2. Built of basswood, it was a little larger than its predecessor and traveled at 50 mph. The RP-3 was introduced a year later. It featured a welded-steel-tube fuselage and recovery parachute and flew at 60 mph.

Only a single example of each of the first three prototypes was built. The first prototype to go into production was the RP-4. Similar to the RP-3, it was upgraded with a 6.5-hp engine driving outrigger-type counterrotating propellers. It moved at 70 mph.

The RP-4 prototype was completed in November 1939. The U.S. Army purchased 53 of these drones, designating them OQ-1.

Meanwhile, in the early 1930s, Denny had hired an electronics engineer, Kenneth Case, to help him develop his ideas for remotely controlled aircraft.

In 1939, Denny founded the Radioplane Company. Two years earlier, he had sponsored a design competition for model airplane engines. Walter Righter, a 1928 graduate of California Institute of Technology, submitted the winning entry. Between 1937 and 1945, Righter designed a built most of the thousands of engines for Radioplane’s target drones. Case and Righter served as Denny’s key technical experts throughout Radioplane’s early years.

In 1952, the company became Radioplane Division of Northrop Aircraft, Inc. A decade later, it was renamed the Ventura Division, the designation by which it still is known today.

Reginald Denny remained active in the Radioplane Company and continued to oversee his model airplane shop until the early 1950s, when he returned to his native country. He died in his home village of Richmond on June 16, 1967, at the age of 75.

OQ-2 drones coming together on the Radioplane Company assembly line in 1941. Note the two propellers on concentric shafts. The parachute hatches are partly open.

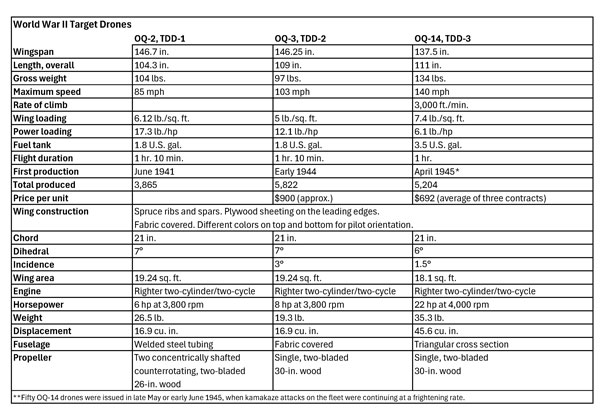

The U.S. Army Air Force actively supported Denny’s efforts to prove the practicality of target drone aircraft. The first Radioplane OQ-2 drones left the production line in a building adjacent to the San Fernando Valley Airport in June 1941. A total of 14,891 drones were produced for the Army and Navy from 1941 through 1945. The accompanying chart details the three designs.

Recovery System: The drones were recovered by parachute. The parachutes featured a 24-foot diameter circular canopy of standard design but used an 18-inch circular vent rather than the standard puckered vent. The main parachute was provided with a standard pilot chute and 24 suspension lines, which were shackled to the apex of four riser cables fastened to four points on the fuselage.

The parachute was packed in a metal tray with canvas flaps and mounted in a welded-steel-tube structure called the parachute hatch. This hatch was hinged at the fuselage top surface and was closed against a spring-tension yoke. Since the rip cord was attached to the fuselage, opening the hatch pulled the cord and released the parachute. An engine ignition switch was activated to the off position when the parachute hatch opened. The hatch was held shut by an electromagnetic relay armature as long as a continuous signal was received on the parachute channel.

Transmitter: The transmitter was large and heavy. It usually was placed on the nearest convenient flat surface and connected to the joystick control box by a cable long enough to give the pilot some freedom of movement.

The output carrier frequency was in the 73 MHz band, with plug-in crystals allowing several transmitters to operate simultaneously in the same area.

The transmitter received its power from a dynamotor unit, which, in turn, was driven by a gasoline generator.

Superimposed on the carrier were five audio signals, as follows:

Command Frequency Action

Right 300 Hz Rudder

Left 650 Hz Rudder

Up 1,390 Hz Elevator

Down 3,000 Hz Elevator

Parachute 955 Hz Lack of this continuous tone caused

release of theparachute after a

one-second delay

There was no proportional control. Both the rudder and elevator moved at a more or less constant rate as long as the appropriate signal was received.

The rudder returned to neutral when the signal ceased. Thus, the pilot had to learn by trial and error how long to signal and when to let go.

The elevator, unlike the rudder, had no automatic neutral, so it locked in position when the signal stopped. Therefore, it was important that the pilot set the elevator properly before launching—and then leave it alone as much as possible. More than one pilot watched helplessly as the drone left the catapult, climbed into a stall, and flew straight into the ground at full speed. All in about two seconds. All because the pilot forgot to check the position of the elevator.

Receiver: The high-gain superregenerative receiver had nine vacuum tubes. It was packaged in an aluminum box about eight inches on a side.

High humidity was the enemy of these circuits, and saltwater was even worse. The Pacific Ocean has plenty of both. On high-humidity days, anything could happen—and often did. I continue to believe that these receivers had sold their souls to the devil.

We grew to hate the sight of a saltwater-soaked plane so much that we took to secretly wiring the parachute hatch shut just before launching. That was my job. If Lt. (jg.) Art Kinney ever reads this, he’ll learn, after 46 years, why at times he just couldn’t seem to get the parachute hatch to open.

Catapult: The Army’s OQ-2 had a landing gear; OQ-3, OQ-14, and all the Navy’s TDDs had none. These later drones were launched from a 37.7-foot catapult by means of electric shock cords driving a carriage with 700 pounds of thrust. The drone left the carriage traveling at about 65 mph. A later version of the catapult, which w received along with the new TDD-3s, contained coiled steel springs in place of the shock cords. Its thrust was said to be 900 pounds. I remember it as being 30 feet long.

There was also a 5-foot catapult with heavy coil steel springs for use on small high-speed boats running into the wind. The strong headwinds were necessary; without them, the drone would be launched into a crash a few feet in front of the catapult.

Engine: The engines had no throttle control. The carburetor needle valve was adjusted for maximum rpm just before launch, and that’s the way they ran—wide open all the time. Some of the runs lasted for over an hour. No wonder the engines were rated for only 50 hours. Actually, I don’t think we ever had one that survived more than two or three hours.

The operating manual warned against letting the engine run for over a minute on the catapult. Without movement, the engine couldn’t get enough cooling air, and at full throttle, it was in danger of burning out. Sometimes we launched as the deadline approached, ready or not.

In a steep dive with the wings level, the engine had a nasty habit of stalling. The solution was to rock the wings during the dive. Don’t ask why. It just worked.

Since the drone had no ailerons, it lost altitude as it banked. After he’d lost a few models, the student pilot usually learned to compensate.

The last and hottest of the World War II drones, the OQ-14 “Bullet” flew at 140 mph on a 22-hp engine. Illustrations courtesy of Northrup Corporation.

SOURCES:

The AMA History Project Presents:

Biography of Reginald Leigh Denny

Reginald Denny, actor, modeler, designer

National Model Aviation Museum Blog

https://amablog.modelaircraft.org/amamuseum/2011/12/20/reginald-denny-actor-modeler-designer

Radioplane Target Drone

National Model Aviation Museum Digital Collections

https://modelaircraft.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/69604A92-2E04-45E9-8027-211817763536

“Prince of Drones” by Kimberly Pucci

Model Aviation, July 2021

www.modelaviation.com/prince-drones-pucci

Comments

Found a tag Radioplane 2895 van nuys

I was metal detecting some area around a model airplane airfield around Simi Valley Moorpark area and came across a metal tag. Radioplane Van Nuys 2895 printed on it. Great to learn more about it. If it means anything to anyone out there please let me know.

Add new comment